Bespoken Word: Tales of co-authoring Gary Fisher's autobiography

In the first of a new weekly column, Guy Kesteven recounts sunshine rides and transatlantic FaceTime calls with a mountain biking legend

We are bike riders.

We are outlaws. Lawmakers. CEOs. Plumbers. Athletes. Aesthetes. Punks. Hippies. Idiots. Geniuses. Tinkerers. Shoppers. Show-offs. Introverts. Tribal. Territorial. Explorers. Creatures of habit.

We ride to get faster. We ride to get thinner. We ride to save our heads from exploding or to empty them entirely. Passionate to the point of religious fundamentalism. Stoically, stupidly stubborn. We race - officially or not. We ride to feel the wind on our faces and through the hair we do or don’t have.

We ride to meet and make friends but sometimes we make the strongest friendships by riding like everyone around us is an arch enemy. We stop to offer help to someone we’ll probably never see again or get real warmth from a squinted nod to a stranger sharing a freezing day.

We, ah damn it, you get the idea by now. We’re a very broad spectrum of sapiens who press pedals often enough to identify as cyclists.

This was really brought home to me when writing a book with Gary Fisher. If the name rings a bell it’s because he was the dude who - together with Charlie Kelly - scrabbled enough diverse touring, road bike, beach cruiser, motorbike, and custom parts together to mount them on a handful of Tom Ritchey hand-built frames and open a shop in California. The shop was called MountainBikes.

Gary doesn’t claim to have invented the mountain bike (well he might have implied that in the past, but he’s older, wiser and a bit less wired now). In 1970s California terms, it was probably Joe Breeze, but knobbled tyred, wide range geared Frankenbikes - some even with sprung suspension - can be found in photos jumping in and out of post WWII Parisian bomb holes. They were crawling over English moors, weaving through the woods of Washington state and doubtless other dirt tracks the world over wherever riders decided to swap their drops for cowhorns. Before WWII - and certainly before WWI - pretty much everyone was an off-road rider by default anyway, as most roads that existed were definitely what we’d call gravel now and tin mugs were the only option.

But anyway, Gary and Charlie set up the first tiny shop you could go into and buy a complete mountain bike from. And crucially it cost an absolute fortune. Their prices started at $1,300 when you could buy a top of the range Colnago loaded with Campagnolo Super Record for less than half that. As a result Gary pulled on the sharpest suits he could find and “sold the shit out of it”. A bunch of early ‘Clunker’ riders racing the clock downhill in Fairfax California got on national TV and Gary made sure he got the last word.

Gary crafted stories for multi-million circulation magazines based on races where, even if you included all the competitors, spectators and any passing dogs, still probably didn’t get into triple figure attendance. He got mountain bikes on the covers of Outside magazine and more importantly he got them on the cover of Time. As he says, he put on a dance that looked so fun everyone else wanted to join in. And it worked. In the US it turned the bike from a toy that was only used (in the US at least) by kids, banned drivers and a handful of masochistic freaks, into a ‘rad’ aspirational, high-tech must-have and it blew up a bike industry that hadn’t changed in decades.

It went properly global too. Not just with riders from every social group and sporting or sedentary background, but the industry as well. The Japanese were desperate to break into the global cycling scene. You’ve got to remember at this point that Shimano had construction rooms that were solely staffed by robots and a wind tunnel for aero testing but they’d never had a single bike with their equipment on in the Tour de France. Companies created by BMX were looking for the next big things. Motocross techs like Richard Cunningham (Mantis/Nishiki), Paul Turner (RockShox) and Keith Bontrager (you can guess that one) wanted something cleaner and less damaging to get involved with. Mike Sinyard was already building touring bikes in Japan and the first Stumpjumpers went on sale just a few months after he bought an ‘accidentally’ misshaped MountainBike off Gary.

As interesting as it is, the ‘mates race, spawns tiny bike shop which the owner detonates into a global phenomenon that revolutionises a totally stagnant industry’ narrative is only a small part of what made working on Gary’s book a fascinating project. In the same way that using our feet to turn a crank and propel a vehicle that stays upright through gyroscopic physics is just a tiny but fundamental part of our stories.

Like most of us, Gary fell in love with riding the first time he flew around a corner to his mate's house when he was four. Not just from the thrill of speed far higher than he could run or the nervous fizz of nearly crashing his knees off. He suddenly had true personal freedom and the easy range to exploit it. While traffic intensity was a lot lower back then, it still wasn’t easy to be a cyclist. Gary still visibly boils about being forced to ride on pavements for block after block by police patrol cars. About being teased relentlessly at school when he was seen out riding in tight shorts and girls' white gym socks to look like the pro riders he’d occasionally seen in borrowed magazines imported from Europe.

While nowadays we have multiple media outlets, WhatsApp ride organisation and cycling-themed cafes to congregate at, when he started racing in 1961 there were only about 200 riders in the whole of the bay area. He laughs when he says their closest outlaw allies on the road were the Hells Angels and they often came to physical blows with drivers. It wasn’t long before his dad was taking the photographs and making posters for local races though and soon the whole family were sucked into the first scene where Gary felt he really belonged.

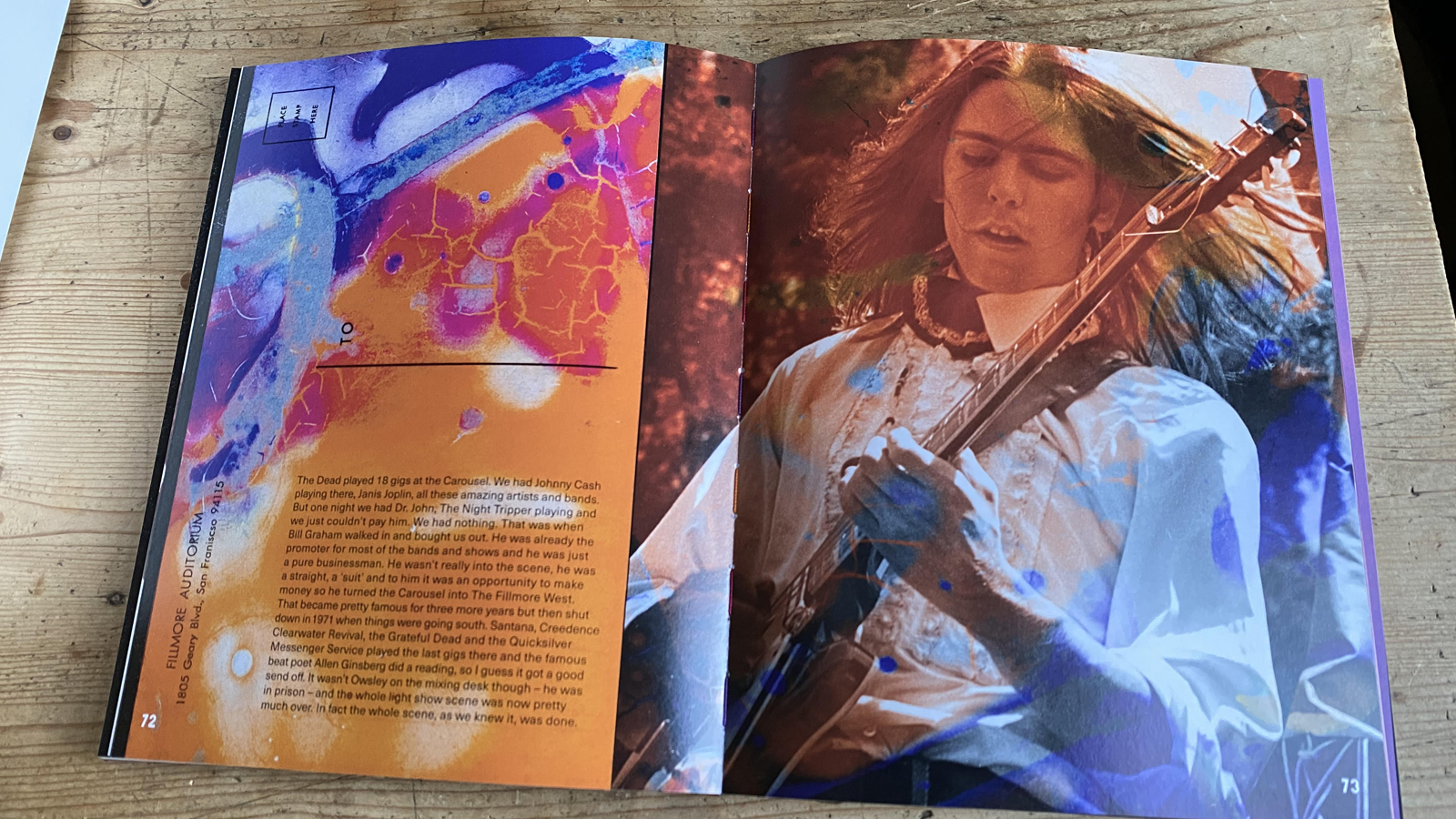

However, just like the tribal groupings of riding today, even that tiny cycling community was divided and defensive. Gary caused waves by turning up on custom ultra-light bikes with Simplex gears and cantilever cyclo-cross brakes because they were lighter than the default Campagnolo spec. The fact he arrived in a van he’d painted pink and he was already hanging out with the Grateful Dead - who he met playing the after-party for a race launch that also visited the Playboy mansion - and building their light shows at the age of 16 probably didn’t help either. The fact his hair was almost down to his collar was upsetting potential sponsors, and eventually got him banned from racing, so for the next few years, Gary chose psychedelic rock over the peloton.

Man, there are some crazy images and stories from those times in the book!

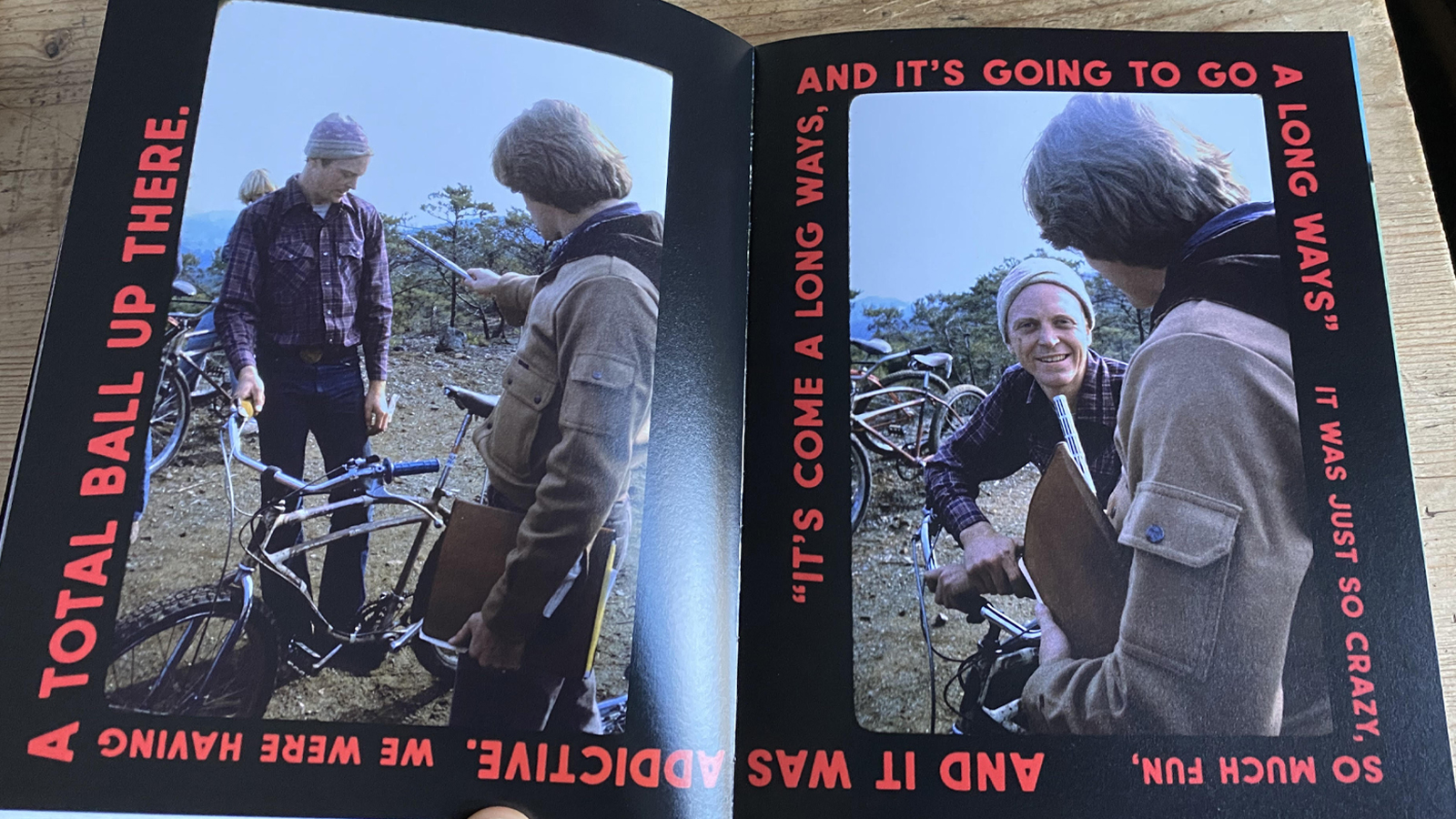

Mind expanded but soul and body crushed by ‘the scene’, it was biking that threw him a lifeline again. He hooked back up with the Larkspur Canyon crew who played and partied on beach cruisers in the foothills of the Californian mountains to escape ‘cars, cops and concrete’. He was introduced to Charlie Kelly because they both had the same Merckx orange Colnago. He started testing and doing tech features for Bicycling magazine and racing road with Greg Lemond and other US upstarts, eventually getting on the long list for the Moscow Olympics that they never attended.

It was fitting a tandem brake, Huret rear mech and Magura motorbike brake levers to a 1930s Schwinn beach cruiser that really got him fired up though. While he admits he was too scared to race the first Repack DH (named because the overheating hub brakes had to be repacked with grease between runs) he was soon in the thick of it and recording the fastest times. The guy who ended up being Jabba the Hutt’s belch was instrumental in getting serious Japanese investment that pulled Gary out of crippling debt and into selling bikes by the container load as fast as they arrived.

Gary’s passion for mountain biking development didn’t slow down for the next decade either and his ability to remember the minute but crucial tech details is incredible. He knows the tubing profiles of an early Excaliber to the fraction, still gets excited about how using Dura-Ace freehubs created a much stronger back end with more tyre space, and regrets pissing off Dia Compe and losing the A-headset hook-up.

His hand will be a blur as he explains how they welded rear dropouts onto fork ends to experiment with handling, optimising it at the 38mm offset which was still the standard till the end of the 26in wheel era. An era that Gary himself was a major part in ending by paying for tire moulds and doggedly championing 29er wheels for several years in the early 2000s despite almost non-existent sales.

How the first designs for the Alembic carbon fibre monocoque full suspension bike were carved by the same artist who made, err, ‘smoking equipment’ for the Grateful Dead.

How getting intoxicated on that project and a return to pro-level racing nearly saw his business totally tank through Taiwanese manufacturing disasters. The crazy story of how he only just saved it by getting Trek on board after hiding in air ducts to hear what his partners were plotting in the office next door.

So yeah, it was a crazy roller coaster ride to document as I interviewed Gary on road rides around Majorca or late night UK/early morning US FaceTime calls. Sifted through ancient race numbers, posters, tech drawings, bike catalogues and photographs of Olympic gold medals and World Championships being won on his bikes to add vivid colour to the fantastic tales.

Gary certainly isn’t done either. While Trek hasn’t had a specific Gary Fisher range for a decade, a lot of the tech he pioneered still underpins their bikes and many others. He’s still flat out busy advising on everything from retail to town bike design, raving about tiny workshops he’d found in Amsterdam and raging that women still have a lousy experience in shops and the pro peloton. He’s a powerful cycling advocate who’s on fire giving keynote speeches on E-bikes to Bosch, opening bike facilities with the mayor of Sao Paolo or leading out World Cup CX race weekends in Wisconsin in a crown and fake fur-trimmed cape.

He goes crazy on the topic of growing racing among kids who don’t fit the conventional team sport profile and how that recruits parents and grows awareness among the top echelon who make the plans. How overhead bike tubes can be designed to create a permanent tailwind for the ultimate urban transport solution. The way resetting the timings on traffic lights can revolutionise cycling take up. Reviving city areas with riders who can literally wake up and smell the coffee as they ride past and are therefore a lot more likely to stop and buy it. How those people - as we all know - will be healthier and happier as a result and how that could potentially change the physical and mental balance of our world.

But above all, working with Gary really reinforced how powerful and wonderful cycling can be, whatever type and level of riding you’re into. Gary might grumble that at 70 years old he can no longer pull a bunch apart by sitting on the front at 300+ watts, but I can confirm he can still turn a serious gear when you’re going through and off into Palma. Every time that FaceTime screen lit up for a book Q and A, he was still wearing his cycling kit from his early morning ride. Face glowing and eyes bright whether it was a steady solo hill session or a burn up with the local ‘dino ride’. As Gary loves to say, “the bicycle is the happiest invention ever made” and working with him on his story was an awesome reminder of just how powerful it can be.

Oh and if you want to read Gary’s book and feast on some fabulous design and images, you can find and buy it at Trek Bikes.

Presuming some people read this (it was the editor's idea, not mine!) I’ll be back again on a weekly basis covering a whole range of random bike-related topics from tech to training and the wonders and frustrations of a life spent testing the latest gear I’m riding for Cyclingnews and Bike Perfect.

I’ll be riffing off nearly 25 years of professional bike and kit-testing experience, and another couple of decades before that from first wobbles to Saturday jobs in bike shops. It’ll cover everything from road to MTB and the ever-expanding grey, gritty area of gravel in between and hopefully it’ll be fun to write and fun to read.

Guy Kesteven has been working on Bike Perfect since its launch in 2019. He started writing and testing for bike mags in 1996. Since then he’s written several million words about several thousand test bikes and a ridiculous amount of riding gear. He’s also penned a handful of bike-related books and he reviews MTBs over on YouTube.

Current rides: Cervelo ZFS-5, Specialized Chisel, custom Nicolai enduro tandem, Landescape/Swallow custom gravel tandem

Height: 180cm

Weight: 69kg