Bespoken Word: Mapping the future

Guy Kesteven talks maps and the teachings of topography

Learning how to read a map is one of the most valuable skills you can learn for any sort of riding. Not only is that truer now than ever before, but it’s also easier. The trouble is, getting wrapped up in a sheet of grid paper covered in squiggly lines and obscure symbols has always had a bit of an identity problem.

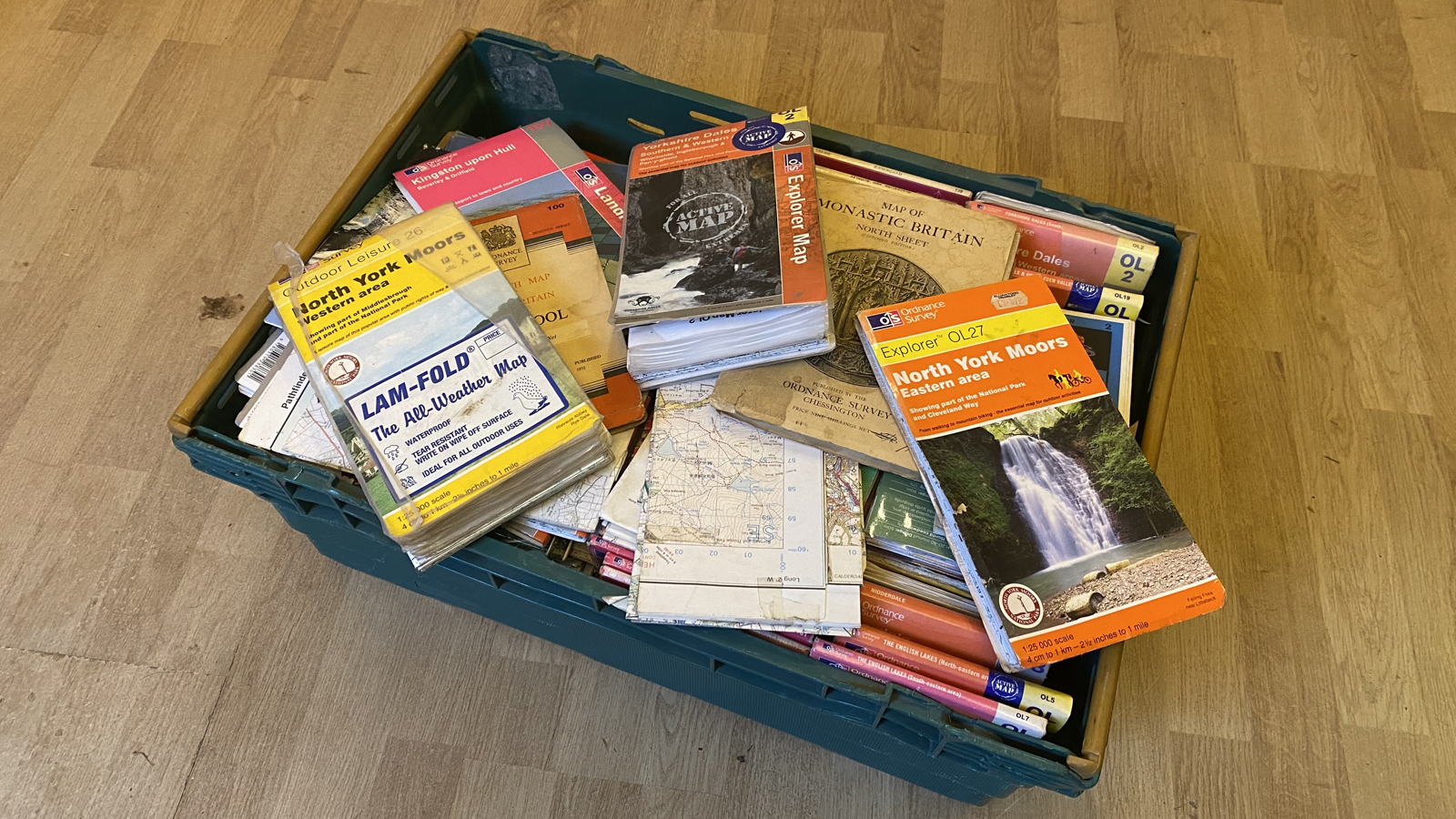

The basic appeal is the biggest problem with map reading. A picture of someone looking at a map will immediately turn most shredders cold. Very few people Instagram shots of themselves shralping a stack of Ordnance Survey’s finest folding gold. For many people, rights of way research and route plotting has a really old-school image of a rider crouching over crumpled paper in the dark - probably with a candle and a wheel building jig in the corner, plus a hint of a beard. Not a fashionably groomed, oiled, hipster beard either, but a haphazard hairy face statement that suggests the owner spends more time developing their 1:25,000 route-finding skills than their 1:1 personal skills.

Thankfully, just like beards, being a map weenie is now becoming a lot more fashionable since gravel/adventure biking has become popular with a fresh population of pedallers. These riders have never done MTB mapping events, a point-to-point Audax or just gone out and got lost for the fun of it, but they are a lot more visible and influential on social media.

And that’s great because it’s about time map heads got some love, as it’s those contour kooks and their routes that have created so many of the trails we ride. I’m not just talking current komoot contributors here, but right back to the prehistoric singletrack savants who sketched a map to a hunting camp on microlithic scraped hide, making sure they avoided congestion on the mammoth motorway. Do you want to know how we know that? Because those double-track ruts you rode over the weekend (and unless you’re Russian or going up a Welsh mountain) has exactly the same track width (just over 4 feet 8 inches) as prehistoric cart ruts found all over Europe.

The intricacies of artisan route planning

Fast forward from time immemorial to TrailForks and you can be damn sure that no trail centers started without sketches on a map. Actually, not just one map, but multiple topographical, geological, land ownership, forestry harvesting schedules and even meteorological overlays are used to create a complete picture of where to put those rolling, swerving ribbons of fun we rely on so much these days.

I get that maps don't help their popularity in some ways. They come with their own weird hieroglyphic language and even folding them back up neatly is an art form in itself. If you apply a bit of patience and common sense to learn what those lines, dots, dashes and other pictograms mean, you’ll be learning the single most useful, transferrable, riding enriching language there is. A skill that’s more useful now than ever given that roads are full of frustrated passing drivers, and you now need to make the most of local potential while avoiding herds of COVID sheeple that are swamping the more commonly known outdoors areas.

Plus - like pretty much everything else - maps have now been synthesized into versions that are easily accessible through your phone and made ridiculously easy to use thanks to orbiting satellite triangulation. Three little words make pinpointing a location easy and memorable rather than an algebraic brain bender. There are also a huge number of route apps available now that take the raw ingredients of the landscape and serve them up as a ready meal.

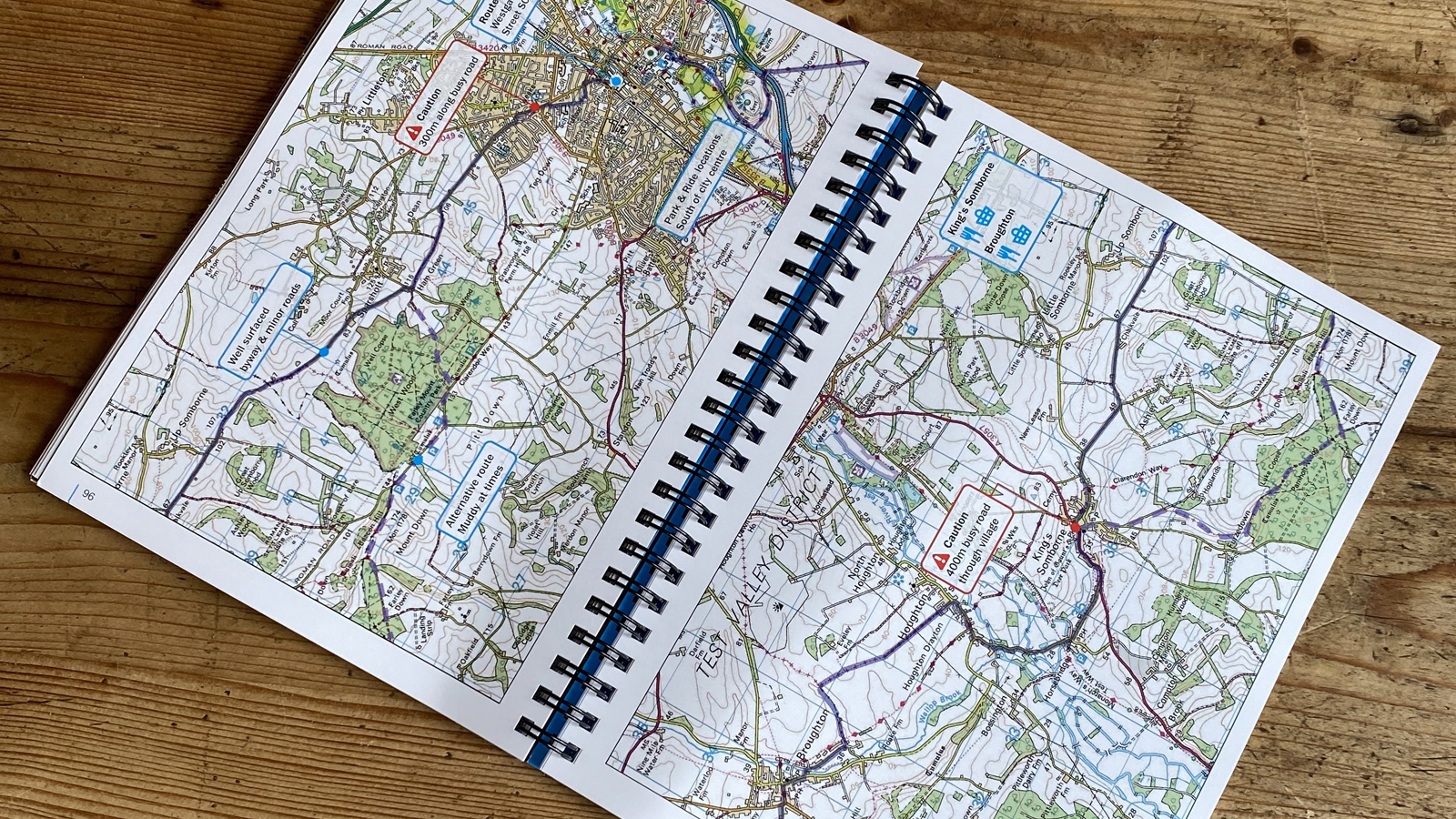

But in the same way that a ready meal is convenient and you will probably find flavors of pre-processed routes that you really enjoy, downloading a dotted line onto a head unit is a very different experience to cooking up a route yourself. Pulling your head out of the pixels and actually understanding what you’re seeing will give you the ability to harness the landscape opportunities around you. Even if the route you’re following is brilliant, you might not even realize that unless you can see it in the context of the wider area. I had the weird experience of writing a written guide for Cycling UK’s new 350km King Alfred’s Way gravel route around the south of England during the country's first lockdown. That meant trying to describe the incredible journey created by route guru Kieran Foster via Google Earth and Street View fly-throughs alongside his notes and an Ordnance Survey dotted line. The genius of the route was only truly revealed when lockdown lifted just in time for a solo recon, and I found myself riding through totally deserted, wild trails that felt like the middle of nowhere when in reality, some of Britain’s densest urban populations and busiest motorways were within a couple of miles. Knowing how to read a map can also save you from ending up at the dangerous end of a shotgun, whether you’re riding or building. It can also help you pick which trail to take to be on the right side of the mountain when the sun starts setting or save you from being properly screwed when your phone/GPS battery dies.

Learning to read

I’m not going to try and teach you to map read here. Not least because this is a global website, so there’s no use telling you exactly which dotted line means what in the UK if you’re trying to work out what’s legal in Ukraine. Also, while I haven’t actually looked, I’m pretty sure there will be some decent YouTube videos on how to learn the basics.

What I want to do is just point you in the right direction. That wasn’t even meant to be a pun either, but that is literally how map literacy starts. Getting a map - or a mapping image on your phone - and looking at it, then looking at what’s in front of you. Shuffle around to a different angle and look again. Maybe switch modes between the map and a satellite image if you’re on your phone. What are those blocks? I reckon you’ll have some 'wow' moments pretty much immediately. The ‘I never knew that bit connected up with that bit’, ‘those bits are so much closer together than I thought’ or ‘why have I never been down there' thoughts.

You might start hitting some language and symbol questions too. Why is that road that color? What’s that ‘radiating line’ emoji, what do contour lines actually mean and how can you tell which direction the slope is going in? That’s hopefully when you’ll realize that you only need to recognize about ten different symbols to keep you away from cliffs and swamps, stop you from getting shouted at for riding on a footpath and that if you follow the contours around you’ll soon find a matching elevation number to check against a neighboring one to work out which way that flat map is sloping

And now the fun really starts, because you can go out and try and link those two ‘closer than realized’ bits together. Follow that newfound road or trail to see what the surface is like, whether it’s fun or what else it can be linked to. Or, because you can recognize the symbol that matches with that distant church or rocky outcrop on top of that hill, you can now track where you are. So when you don’t bother to look at the map for a bit, or just decide to go out and get lost, you can get unlost again without a rescue helicopter being involved.

If you really start to get into your mapping, it might also make you curious about what other things it can tell you. Maybe that church sits alongside a prehistoric henge or inside the embankments of a Norman or Roman fort. You’ll spot mills, mines, linking paths between monasteries or cattle markets. Or maybe you’ll start getting your rocks off on the underlying geology and geography and realize that oxbow lakes are actually kind of cool.

Unlike most things, bike-related maps are a totally universal resource that works for road, gravel, mountain biking, running, dog walking or just escaping into the possibilities of future adventures when weather, lockdown, tiredness or time mean you can’t ride where you want for real. That’s the other great thing about maps, they’re a picture story with whatever content and ending you want. I can still spend hours staring at my tattered local Ordnance Survey Landranger and still find fresh interest decades after I first learned to fold it back up properly.

Guy Kesteven has been working on Bike Perfect since its launch in 2019. He started writing and testing for bike mags in 1996. Since then he’s written several million words about several thousand test bikes and a ridiculous amount of riding gear. He’s also penned a handful of bike-related books and he reviews MTBs over on YouTube.

Current rides: Cervelo ZFS-5, Specialized Chisel, custom Nicolai enduro tandem, Landescape/Swallow custom gravel tandem

Height: 180cm

Weight: 69kg